Incident Management from Scratch - Introduction Part 2 -

This is Tanaka (@tako_sonomono) from the Service Reliability Group (SRG) of the Media Headquarters.

The #SRG (Service Reliability Group) mainly provides cross-sectional support for the infrastructure of our media services, and is responsible for improving existing services, launching new ones, contributing to OSS, and more.

Introduction"Resolution" required by incident ownersThe complete incident lifecycleIssues and solutions during the operation phase1. Single Source of Truth2. Designing communication channels3. Ticket renewals have become a mere formality and are becoming too strictConclusion

Introduction

Last year's articleWe discussed the establishment of an "incident owner" and "incident commander" in incident management, as well as the "triage" decision-making process.

These were discussions of the "points" in the initial response to an incident, but this time we will delve into the "line" leading up to the subsequent resolution, that is, the definition of the workflow, and the operational challenges involved in implementing it in an actual organization.

In this article, we will explain how incident owners should gain a high-resolution understanding of existing flows, as well as the challenges they will face in communication design and recording once operations begin, using SRE principles as a starting point.

"Resolution" required by incident owners

From an SRE perspective, one of the elements of effective incident management is a "Defined Process." Clear procedures agreed upon in advance are essential to reduce cognitive load during an emergency.

The basic premise for an incident owner is that they must have a more accurate understanding of the existing flow than anyone else in the organization. This is because the unique rules and collaboration specific to that business, which do not appear in a general-purpose framework, always have a historical and business background (Context). Without a complete understanding of this, the commander will not be able to guide the actions of team members, nor will they be able to provide a rational answer to the question, "Why is that procedure necessary?"

To improve understanding and prevent it becoming too personal, we recommend that you first illustrate the workflow in your own words and document it as a Playbook.

The complete incident lifecycle

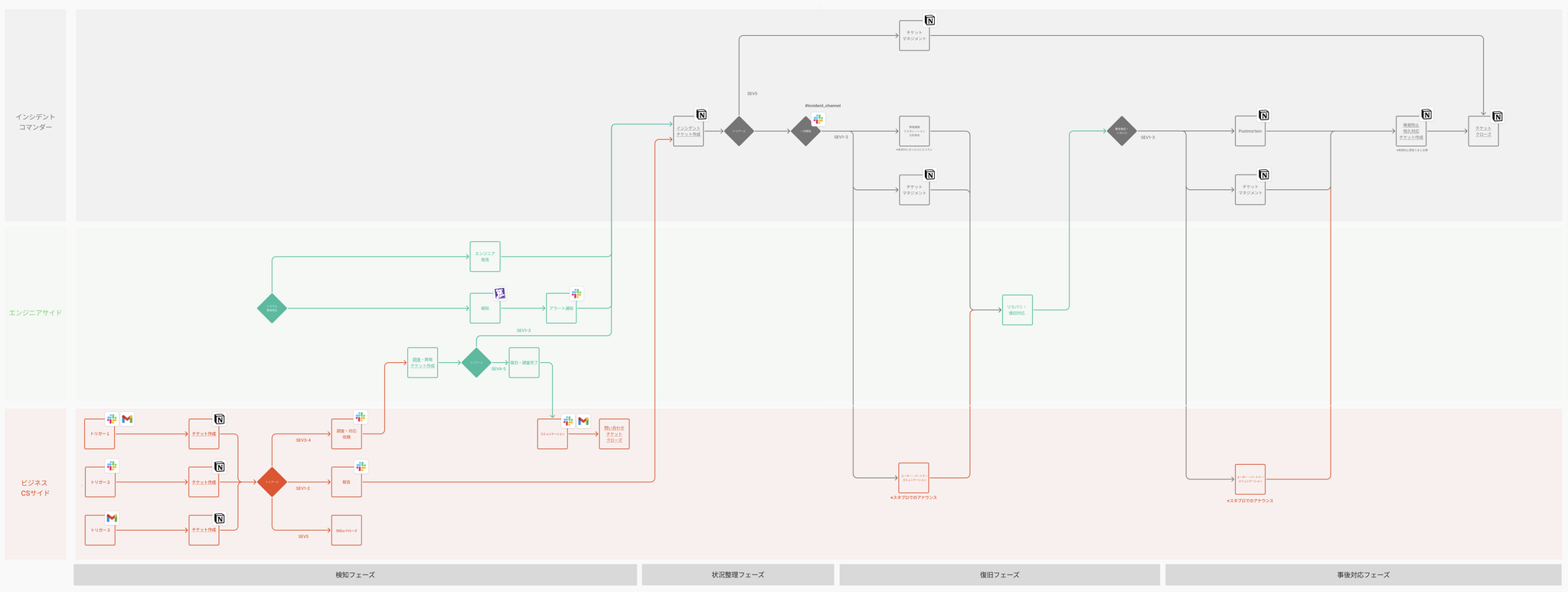

Incident flows vary depending on the size of the organization and the nature of the business. As an example, the incident flow for a specific business at Amebalife can be broken down into the following 13 phases at a practical level.

- Problem occurs: User impact or system abnormality onset

- detection: An alert is fired or an inquiry is sent to CS

- reaction: Recognition by on-call personnel and CS

- Ticketing: Raising an incident in an incident management tool (Jira/ServiceNow, etc.)

- triageIdentifying the scope of impact, determining SEV (severity), and establishing a system

- primary report: First report via communication tools (Slack, etc.)

- User Communication: Report an outage (update the status page, post a notice)

- Recovery response: Investigation, Fix creation, Deploy

- Temporary restoration: Service level has returned to an acceptable range

- User Communication: Recovery report (status page updated, announcement posted)

- Postmortem: Retrospective, RCA (Root Cause Analysis)

- Permanent response: Implementing measures to prevent recurrence

- Close: Ticket completion

What's clear from this flow is that incident response is not limited to the engineering domain.

In particular, collaboration with CS, PR, and the business side in Phases 7 and 10 is just as important as system recovery in terms of "service reliability from the user's perspective."

*The actual workflow created

It is recommended to create separate flows for each segment (IC/Engineer/Business)

Issues and solutions during the operation phase

Even if you define an ideal flow, the uncertainty of "human" becomes a bottleneck in actual operation. This article describes the main challenges you will face after starting operation and the approaches to overcome them.

1. Single Source of Truth

You can use any tool to manage documents such as operational flows, tips, and contact lists, but discoverability is important. These documents must be placed in a location that can be easily accessed in an emergency.

2. Designing communication channels

The location of the War Room for discussions during incident response is a trade-off between information transparency and catch-up costs.

- In the ticket: Highly recordable but not immediate.

- Slack threads: Easy to use, but readability drops significantly as the amount of information increases.

- Dedicated Slack channel (Spot): Recommended

For incidents with a high SEV (high impact), a dedicated Spot channel should be created and information collected there. This is recommended from a "cognitive load" perspective.

Discussions in Slack thread format can be difficult to follow chronologically, increasing the cost of catching up for supporters and decision makers who join later. Dedicated channels separate information noise and make it easier to integrate bots such as ChatOps.

3. Ticket renewals have become a mere formality and are becoming too strict

Many organizations face the situation where they don't have time to update tickets while they are responding to an incident. However, if ticket updates are delayed, sharing the status with stakeholders will be delayed, resulting in an increase in individual inquiries (interrupting tasks) to engineers.

It also reduces the quality of future data analysis and postmortem.

It's not realistic to force complete manual synchronization to address this issue.

This should be seen as a type of toil that SREs must eliminate.

We are currently working on establishing a workflow for "automatically generating summaries and updating tickets from Slack interactions and conversation logs."

Conclusion

This time, we have organized the process definitions and operational issues in incident management.

When promoting incident management, it is tempting to prioritize tool selection, but the essence of incident management lies in whether the incident owner accurately grasps the "current situation (As-Is)" and can identify where the bottlenecks lie. Based on the premise that "people cannot autonomously perform operations that involve organizing information," the focus of future incident management will be on how to utilize systems and AI to ensure the reliability of processes.

If you are interested in SRG, please contact us here.